Simple Machines

Now we know what a computation is, but how is that related to the computers we know today?

To answer this question, we are going to go way back to the beginning and talk about the very first computers: people. People have been carrying out computation for quite some time, especially for business purposes. The faster and more accurately you can compute, the more products you can sell, the better you can track your finances, the further you can plan for the future, etc.

Humans are decent at computation (almost all of pre-college math is computation), but humans come with some significant drawbacks. The main problem is that computation is very boring. Since computation relies on algorithms—instructions with no room for interpretation—it can be very uncreative, dull work. Dull work causes people to zone out; zoning out causes people to make silly mistakes. Secondly, humans do not have very good memories for computation. We can remember lots and lots of things, but our memory is fuzzy and selective: not so good at remembering huge quantities of precise numbers. That means that large computations require a lot of book-keeping to bypass our limited memory. Lastly humans are not terribly fast at computation. For big companies with lots of accounting requirements, humans are not a great solution.

Various computational tools have been invented over the years to assist humans with computation—such as the abacus and slide rule—but these essentially amount to fancy book-keeping methods and still require slow, fallible human effort.

The big breakthrough in computation came with computing machines. This was a crucial stepping stone to modern computers, so we are going to reinvent it right now by creatting a machine that can add two numbers with much less chance of human fallibility mucking it up. We are going to work our way up to this machine by making much simpler machines first.

We will start with a wheel attached to the surface of a table. Around this wheel we will evenly write the digits 0–9 in order. We can attach a handle to the wheel for rotating it and draw a mark on the table to point at a digit on the wheel. Voilà: we now have a very simple computing machine! In particular, this is an “add 1 to a number” machine. It takes as input a single digit number and outputs a single digit number. The algorithm it uses is as follows:

- Turn the wheel so that the mark points at the input digit

- Turn the wheel clockwise so that the mark points at the next digit

- The digit pointed to by the mark is the output

This machine is a bit silly, but it does do the job. In particular, it saves you the enormous effort of remembering what order the digits come in: you simply find the digit you want to add to, turn the crank, and read the result. This is a simple “add 1 to a single digit number” machine!

But what happens if we give it 9 as input? The wheel circles back around to 0!

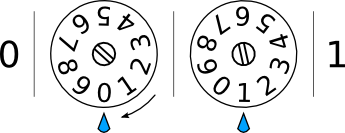

We can solve this problem by adding another wheel to our contraption. The second wheel is similar to the first but with one crucial difference: rather than turning it directly with a crank, it is attached to the first wheel. The attachment turns the second wheel only when the first wheel turns from 9 back to 0 (the diagram below shows a crude example of this, but if you want to see how this is done for real check out this video). Now when we give an input of 09, turning the handle changes the 9 to 0, which advances the second wheel from 0 to 1 and we get 10. Success! If we keep turning, the second wheel remains at 1 (giving us 11, 12, 13, …) until we get to 19 and it once again advances to 20. We now have a machine that can add 1 to a two digit number!

By now you might realize that we still have a problem. Our new machine works all the way up to 99 and then the same error occurs. Turning the rightmost 9 back to 0 advances the leftmost 9 to 0 as well, so our machine says that 99+1=00. Dang. We can keep adding more wheels like we did before. A third wheel will work all the way up to 999, but again we will have the same problem: more wheels only delays the error. How do we solve it? Well… we cannot. Without having infinitely many wheels, there is nothing we can do other than ensure that we have enough wheels at the moment to handle the input we have. You might be surprised to know that—as simple as our little machine is—it shares this problem with every modern computer. It is such a common problem that computer scientists even have a special term for it: “overflow”. As is common in computer science, from now on we will just assume that we have lots and lots of wheels—not infinitely many, but enough that we can handle reasonably large numbers without overflowing.

It is tempting to think of overflow as a problem like I just did. But there is another way to look at it. What if we thought of our machine as taking your input and output, dividing them by 100 and then only showing you the remainder?

99 + 1 = 100; 100 ÷ 100 = 1 with remainder 0

If that is the rule, then 99+1=0 is actually correct. Do a few more examples and you will see that this always works:

99 + 2 = 101; 101 ÷ 100 = 1 with remainder 1

99 + 3 = 102; 102 ÷ 100 = 1 with remainder 2

And so on. This trick is called “modular arithmetic”. You can add, subtract, and multiply just like in normal arithmetic except that the answer always stays smaller than the “modulus” (which is 100, in this case).

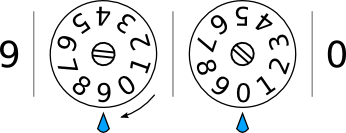

If we use the right sort of mechanism to connect the wheels (as I did in the diagram), we get a bonus feature from the machine: turning the rightmost wheel backwards one digit from 0 to 9 turns the wheel to its left backwards by one digit (the reverse of what the wheels did before). Now we have an “add or subtract 1 from a two-digit number” machine. By turning the handle in the opposite direction, it counts in the opposite direction from what it did before. As you might expect, this machine now has an “underflow” problem: if we subtract 1 from 0, the rightmost 0 turns to a 9, which turns the wheel to its left from 0 to 9, which turns the wheel to its left from 0 to 9, until every wheel is set to 9 (giving the largest number the machine can display). Again, this problem is unavoidable.

We are now ready to construct our number adding machine. To construct it, we take two of our add/subtract 1 machines and connect them such that the two wheels with handles turn each other in opposite directions. Now when we add 1 on one machine, it subtracts 1 on the other machine and vice versa. Operating this machine is quite simple:

- Manually turn the wheels of each machine to display the two input numbers

- Turn the handle until one of the machines is all zeroes

- The other machine now shows the sum

This machine solves a lot of the problems with human computation. Short of inputting the numbers incorrectly or misreading the output, it’s virtually impossible to make a computational error. It can compute as quickly as the operator can turn the handle (if it is well built). It does solve the problem of humans’ limited memory, however it exchanges it for its own memory problem: the over/underflowing we noticed earlier. This isn’t as bad though: we’re limited by the machine’s memory (number of wheels), but we know exactly what that limit is, so we know which numbers it isn’t able to handle.

We do have some new problems though. Building a physical machine out of gears and levers is no simple task, especially since a high degree of precision is required for good operation. With use this machine would slowly deteriorate and need to be serviced and supplied with replacement parts. Also while humans can be taught and trained to perform any kind of computation, this machine had to be specially designed to perform our one, specific kind of computation. If you wanted to build a machine that multiplied numbers or one that performs exponents, you would need to design and manufacture a whole new machine from scratch. Ugh. Still, for a while these sorts of machines were quite widely used. The German Enigma encryption machine used in World War II is a particularly famous machine of this class. The Enigma used electricity to power light bulbs, but otherwise functioned similarly to our wheel-based adding machine.

Computers

The capability to break the Enigma code was thanks in part to a brilliant English mathematician who had dreamed up a new sort of computing machine. He wondered if you could build a computing machine that computes computing machines: a machine where the input would not only be numbers, but the type of computation to perform as well. That is, by changing part of the input you could have the machine perform a completely different computation on the same numbers. Such a machine would solve the biggest problem with previous computing machines: the need to design and manufacture a new machine for each type of computation. Such a machine would—in a sense—be the last computing machine you would ever need; it could be adapted to solve any computable problem simply by changing its input.

The machine he created, and which now bears his name, is the Turing machine: the first true computer. In order to create the mother-of-all computing machines, Dr. Alan Turing distilled computation to its bare essentials. The machine consists of the following components:

- A tape, on which we can write a sequence of digits, which serves as the machine’s memory. As with the number of wheels on our adding machine, we assume that the tape is very long—long enough for whatever computation we are performing. We assume that the tape starts with every position in the sequence set to 0

- A head which can read and write digits on the tape—but only one digit at a time. The head can move along the tape to go from one digit to the previous or next, but again only one digit at a time.

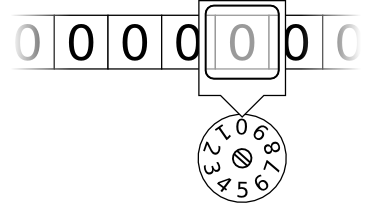

- A state register, which we can think of like a wheel in our adding machine. The wheel has numbers around the edge and a mark pointing at a single number. Whatever number is currently pointed to, we call the “current state” of the Turing machine. Similar to the tape, we don’t care how many numbers are around the edge of the wheel. It just needs to be enough to perform the computation we’re doing. We assume that the machine starts in state 0.

-

A list of instructions for the head to follow. However, every single instruction must be a rule of the form:

- Read a digit from the tape, and depending on this digit and the current state,

- Write a digit to the tape (it could be the same one we just read),

- Move the head either one symbol to the left, one symbol to the right, or not at all,

- And choose the next state of the machine (again, this could be the same state it was already in)

Let’s compare this to the mechanical adding machine we recently built. The tape is a lot like the series of wheels. Each wheel pointed to a single digit, just as each position on the tape can have a single digit on it. The head is kind of like you, looking at the wheels and turning the crank until the computation is complete. The list of instructions is an algorithm just like the instructions for operating the adding machine. The big difference is that these instructions must all be the same format: read a digit, write a digit, move, change state. Noticeably absent from our old adding machine is the state register. We’ll see how that works in a moment.

To show you how a Turing machine can replicate any other computation machine, we’ll recreate our amazing “add 1 to a number” machine with a Turing machine.

First we’ll give the machine input: we take our tape of all zeros, erase a few of them, and write our number in their place. We can write our number such that the rightmost digit is under the head of the machine. For this computation, we will only need two states, so our Turing machine should have a state register with at least states 0 and 1 on it.

Now we need to give it a list of instructions. Remember that all Turing machine instructions look something like, “If the current state is 1 and you read a 0, write a 3, move to the left, and change the current state to 2.” Another instruction might be, “If the current state is 1 and you read a 1, write a 0, don’t move, and change the current state to 9.” Notice that of all those words, instructions can only differ in a few ways. To keep things brief we’ll write instructions in shorthand:

(current state, digit that was read, digit to write, direction to move [L/R/N], next state)

In our shorthand those last two instructions would look like this:

(1, 0, 3, L, 2)

(1, 1, 0, N, 9)

Back to the add 1 machine, here is our list of instructions:

(0, 0, 1, N, 1)

(0, 1, 2, N, 1)

(0, 2, 3, N, 1)

(0, 3, 4, N, 1)

(0, 4, 5, N, 1)

(0, 5, 6, N, 1)

(0, 6, 7, N, 1)

(0, 7, 8, N, 1)

(0, 8, 9, N, 1)

(0, 9, 0, L, 0)

Now we can imagine how our Turing machine will operate. Suppose we give it 4 as input:

- The machine starts in state 0 and reads a 4. This matches the rule (0, 4, 5, N, 1) so it writes a 5, doesn’t move the head, and changes to state 1.

- The machine is in state 1 and reads a 5. There are no rules that start with (1, 5, …) so the machine stops.

Lo and behold there is now a 5 on the tape. Amazing! Okay, maybe not that amazing. Perhaps an input of 299 will be more mind-blowing:

- The machine starts in state 0 and reads a 9. This matches the rule (0, 9, 0, L, 0) so it writes a 0, moves the head to the left one, and changes to state 0.

- The machine is in state 0 and reads a 9. This matches the same rule as before, so it writes a 0, moves the head to the left one, and changes to state 0.

- The machine is in state 0 and reads a 2. This matches the rule (0, 2, 3, N, 1), so it writes a 3, doesn’t move the head, and changes to state 1.

- The machine is in state 1 and reads a 3. There are no rules starting with (1, 3, …) so the machine stops.

Bam! Our Turing machine wrote 300 on that imaginary tape like a boss.

Have you figured out the purpose of the state register yet? It comes from how addition works with single digit numbers. In most cases, when you add 1 to a single digit number you just change it to the next single digit number and you’re done. The exception is when you add 1 to 9, then you change it to a 0 and have to add 1 to the next digit as well. So you can think of state 0 in the register as being the “add 1 to this digit” state. Look back at the list of instructions; every rule starting with (0, …) says how to change that digit when 1 is added to it. The 1 state is our “finished” state. No rule starts with (1, …) so when we change to that state the machine will stop. Every instruction transitions to the finished state except for the rule (0, 9, …) because then we need to keep adding. Cool, right?

The state register is one piece of the magic of Turing machines. Even though it’s just a bunch of numbers, the way we use those states in our instructions gives them special meaning. You could write different Turing machine instructions also using states 0 and 1, but with completely different meanings than they had in our last example.

An algorithm that is read and performed by a computer is called a program. Programming is the process of inputting the algorithm into the computer for it to read.

In the vernacular of superusers, you could call the list of instructions an “Add 1 to a number program”.

Exercises

- Create a list of Turing machine instructions (i.e. a program) for subtracting one from a number. Test your program using 4 as input and again using 100. Now try subtracting 1 from 0. What will happen? Think about different ways you might avoid this problem.

- The Turing machine I described uses digits and numbers for the tape and state register but these were actually an arbitrary choice. What if we upgrade our Turing machine to read and write letters in addition to digits? Can this help solve the problem in the Exercise 1?

- The add 1 program is really repetitive. Try to think of a way to change the program and input we give the machine so that we don’t end up with 9 versions of basically the same instruction.