Hardware

By now you should have a decent grasp of the theory behind computation and what makes a computer a computer. But the tiny theoretical machines we’ve been playing with are nothing compared to the fearsome computers we use in this information age. How do those work? Unfortunately the answer is very, very, very complicated. So we’re going to skip over a whole lot of details (yay!) because frankly most superusers don’t know this stuff anyway and often don’t need to.

But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t care about learning those omitted details! Remember: every tidbit of knowledge about computers is of interest to a superuser. Some tidbits are just more interesting than others.

Virtually every modern computer is made of several interconnected and swappable pieces. Each piece has a different responsibility. This is handy because if a piece breaks or isn’t working well, we don’t need to throw out the whole computer—we can instead swap out the offending component. For some less important pieces, the computer might even continue operating in the event of a failure. Like so many other things, we have special computer lingo for these pieces:

The physical components of a computer are called the computer’s hardware.

This is in contrast to the other essential components of a computer:

The programs run by a computer are called the computer’s software.

There is a huge variety of hardware available for computers these days, so in this chapter I will focus on only the most common ones. Now put your hands together as we welcome our players to the stage…

Central Processing Unit

Often called the “processor” or “CPU”, this component is the beating heart of your computer. It performs almost every calculation of the computer, and it does so at a mind-bendingly fast speed. The CPU is very much analogous to a Turing machine. A Turing machine’s memory is the tape on which it writes digits; a CPU’s memory is its “registers”: a collection of numbers each with a specific size (32 bit, 64 bit, etc.) and silly names like “EAX” or “XMM0”. The CPU performs algorithms by following instructions—just like a Turing machine. An example of a CPU instruction might be “store the 32-bit value 0xF4285BC0 in the register EAX” or “add the value in RBX to the value in EAX and store the result in EAX”. A Turing machine has a moving head to perform the algorithm’s instructions; in a CPU the equivalent component is called the “core”. Many modern CPUs have multiple cores, allowing the CPU to process several instructions at once! Some of the duty of the Turing machine’s state register is performed by special registers in the CPU while other aspects of the state are handled by other components (as we’ll see later).

While a Turing machine only accepts one type of instruction, CPUs have a wide variety of instructions that they understand. This makes the design of the CPU more complicated, but makes program design much simpler. The type of instructions understood by the CPU vary by model and manufacturer. This means that each program needs to be designed for a certain instruction set—and only CPUs that know those instructions will be able to run those programs. This is one of the big difficulties of program design.

CPUs are measured primarily in three ways: speed, parallelism, and memory. Speed is the one you’ll hear about most often. CPUs read instructions following a very rigid timer called the “clock”. The faster the clock speed, the quicker the CPU can finish each calculation. But there are limits to the clock speed: set it too fast and the calculations can become error-prone or the CPU can overheat and damage its physical components. All CPUs come with the clock speed set at a safe value by the manufacturer, but some risk-taking superusers choose to override it and “overclock” the CPU to perform faster. The usual measure of speed is hertz. A 1 hertz CPU can perform one program instruction each second. An average CPU at the time of writing is clocked at about 3.5 gigahertz; that’s 3.5 billion instructions per second. That is rather fast indeed.

Technically speaking, a hertz is a “per second”. So we should really say that CPU speed is measured in “instruction hertz”—instructions per second. But no one says that. Ever.

The second measure, parallelism, is just a count of how many cores a CPU has. Four core CPUs (AKA quad-core) are becoming quite common these days. Parallelism is a very appealing idea because you might think that it multiplies the speed of a CPU: a CPU that performs four instructions at once will run a program four times faster. But the reality is less exciting. It turns out to be very hard to create algorithms that still work when four instructions are processed at once, thus many programs ignore additional cores and use only one core at a time. However, we are getting better at taking advantage of multiple cores so single core CPUs are becoming less common.

The final measure, memory, is mentioned much less often but is still crucial. With our Turing machines, we were allowed to have as much imaginary tape as we wanted, which was convenient but unrealistic. With a CPU, the number and size of available registers is set in stone and the total capacity is not very large. To help with this, most modern CPUs have a “cache”—an extra chunk of memory (usually a few megabytes) for storing additional information. The limitation of the cache is that it can only store information. If we want to use a number in the cache for a calculation, it must first be transferred to a register. This makes using the cache slightly slower than the registers, but the extra size makes it worth it.

Random Access Memory

Often called just “memory” or “RAM”, this component stores most of the information needed while your computer is in operation. Compared to the size of the registers and cache of the CPU, the RAM is massive—usually measured in gigabytes (remember, that’s billions of bytes). However, accessing information in the RAM is even slower than accessing the CPU cache. But again, the increase in storage capacity makes it worth it. The RAM is where the programs are stored before the CPU performs them, and it also performs much of the duty of the Turing machine’s state register, keeping track of the state of the programs as the CPU does all the work.

You might be wondering what is “random” about the RAM. Imagine the information in your computer as a bunch of books. The CPU reads the books in order to do its work, but it can only hold a few books at a time. In this analogy, the RAM is like a big bookshelf. What happens when the CPU needs its copy of “The Golden Compass”? The computer could find it by starting at one end of bookshelf and running its finger along each spine until it spots the requested title. This would be what computer scientists call “sequential access”—the computer looking at each book in sequence in order to find a specific one. But sequential access is slow; the more books you have, the longer it takes to find a particular one. If the CPU needs a lot of books at once, it can only get them quickly if they happen to be near each other. RAM is a much more clever bookshelf. It is designed in such a way that the CPU could start calling out book titles randomly and the RAM would be able to retrieve them just as quickly as if they were all sitting together at the front end of the bookshelf.

RAM is easy to measure: you want a lot of it (about 4-16 gigabytes at the time of writing) and you want it to be fast.

Now the RAM has one big deficiency: it’s volatile. That means it can only store information while it is powered by electricity. To continue the previous analogy, the RAM is like a bookshelf without the shelf. When the CPU hands over its copy of “The Amber Spyglass”, the RAM dutifully puts it in place, and it immediately starts falling to the floor. But the RAM is so very speedy that it can grab each book before it hits the ground and put it back in place, over and over again while your computer is running. But as soon as your computer is powered off they all clatter to the floor and that beautifully organized information is lost.

But what about all of your personal files? Your don’t lose all of them when you turn off your computer. Where are they stored?

Hard Drive

People these days have a lot of data. Music, movies, and games can quickly add up to be hundreds of gigabytes of information—far too large to even store in your RAM (ignoring the problem of volatility). To solve this problem, we need large, persistent data storage. The hard drive fills this role.

There’s some confusing terminology here, and to understand it we need to quickly recount the history of data storage. In days of yore, it was common for personal computers to store information on flexible magnetic disks. By spinning the disk around, the computer could read information from different portions of the disk. For example you would store a program on such a disk, plug it into your computer, and the program would be transferred to your RAM for the CPU to read. These disks were affectionately referred to as “floppy disks” and they were cheap but couldn’t store much information. Often we had to break data down into smaller chunks and store them on several floppy disks, which was a major inconvenience.

The situation improved with the creation of hard disks. These were magnetic like floppy disks, but made of thick metal and were capable of storing much more information. Hard disks could store essentially as much information as you could want but were larger and more complex. Because of this, hard disks were usually used as permanent fixtures in computers rather than swapped out frequently like floppy disks. The motorized components that drove the spinning of the disk and read and wrote information to and from it were included with the disk as a single package. Hence, these storage devices were called “hard disk drives” or “HDD”s for short.

Similar to the story for RAM, it is even slower to read and write data to a HDD but the huge increase in storage capacity makes it worth it. By now you might notice a pattern:

Registers → Cache → RAM → HDD

Each transition trades speed of access for increase in capacity. This is one of the biggest differences between a theoretical computer like a Turing machine and a real computer. In theory, a computer only needs a single type of memory—but by having multiple types with different speeds and capacities we can make computers run faster and more efficiently.

And since we’re always searching for faster ways of doing things, HDDs are currently on their way out of the door. The replacements are called solid-state drives or “SSD”s. They perform the same duty as HDDs, but are physically smaller, require less electricity to operate, and operate much, much faster. SSDs also don’t use disks or have motors and moving parts like HDDs do. However, despite SSDs’ growing popularity, it is still common to refer to the permanent storage device in your computer—regardless of its type—as the “disk” or “hard drive”.

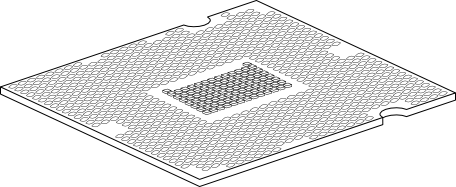

Motherboard

All of these components need to be able to communicate in order to transfer data between them. The motherboard or “mobo” fills this role. Motherboards have a variety of connectors to which the CPU, RAM, hard drive, and other computer peripherals attach. The CPU connector, or “socket”, is often the most important. While the RAM and hard drive connectors are generic enough to work with a variety of models, the CPU socket usually restricts your choice of CPU to only a few types.

Additionally, the motherboard contains the simple programs and data required to start your computer. These programs recognize all of the components attached to your computer and initiate the loading of more complicated programs and data from the hard drive.

The programs stored on the motherboard that control and initiate the other computer components are called the Basic Input/Output System or BIOS.

Because the motherboard mostly acts as a middleman between more complicated components, it is often the cheapest part to buy. But its central role also means that a faulty motherboard is one of the more problematic issues a computer can have.

Other Components

The components mentioned so far are what I would call the “essential” components of a computer. You will find them in almost every computer. However there are a number of additional components that we expect many modern computers to have.

Monitor

Often called the “display” or “screen”, the monitor provides a means for the computer to create digital images. All monitors display images using a grid of tiny pixels.

A pixel is a square with a solid color.

If the pixels are small enough, our eyes lose sight of the grid and it becomes possible for monitors to display images that look smooth. If the monitor can change the color of the pixels quickly enough, a series of images can be displayed as an animation—much like a flip book.

Monitors can vary in many ways:

- The size of the monitor (usually bigger is better)

- The number of pixels (more is better)

- The size of the pixels (smaller is better)

- The number of colors that each pixel can have (more is better)

- The range of color that each pixel can have (e.g. some monitors can display darker or lighter colors than others)

- How quickly each pixel can change color (faster is better)

- The type of connections the monitor can use to connect to the rest of your computer

Graphics Processing Unit

Often called the “graphics card”, “video card”, or “GPU”, this component is specifically designed to provide image data to the monitor. You might find it odd that such a specific component exists, but consider the example of typing an e-mail on the computer. We expect to be able to press a key on the keyboard and for the letter to instantly appear on the monitor. Humans are perceptive enough that if it takes more than a few hundredths of a second for the letter to appear after pressing the key, we notice the delay—and this can make the computer very frustrating to use. Consequently, your computer is constantly racing to quickly display images on the monitor before you notice—in addition to all of the work it’s doing to run your other programs. For demanding tasks like simulating three-dimensional scenes or displaying high-detail videos, the CPU can have a hard time keeping up with the workload.

The GPU makes life easier for the CPU by taking over all image-related processing. It’s basically a separate computer inside your computer, with its own CPU and RAM—both of which are specially designed to quickly perform the most common calculations required for producing digital images. The GPU’s complexity can make it one of the most expensive components of the computer.

Sound Card

Much like the case of the GPU and the monitor, the sound card provides audio data to the computer’s speakers—allowing for near-instantaneous audio responses to our actions. However, due to the relative simplicity of audio processing and the rising power of CPUs, it is becoming more common for the motherboard to include its own speaker connections and for the CPU to perform all audio-related computation.

Dedicated sound cards these day are mainly useful for audio engineers or those with advanced computer speakers.

Network Interface Controller

The ability for computers to communicate with each other is kind of a big deal these days. This component, often called the “NIC”, “network adapter”, or “LAN adapter” (LAN being a specific type of network), facilitates such communication. It provides the connection with the network—which could be a plug for a wire or an antenna for wireless networks—as well as hardware for decoding and interpreting the information received over the network.

With the ubiquity of computer networking and the increased power of CPUs, it is becoming more common for the motherboard to provide its own network interface and for all network-related computation to be performed by the CPU.

Universal Serial Bus

This one isn’t actually a component at all, it’s a standard. But you’re probably already familiar with it from its acronym: USB. In the dark ages of computers, there was very little standardization among computer components. There were more specialized cables and connectors and things were generally not very interchangeable. With USB, several computer companies collaborated to create a computer connection that would be generic enough to work for a variety of purposes. These days every motherboard comes with at least a couple USB connectors and USB is used to connect keyboards, mice, web cams, printers, joysticks, hard drives, phones, cameras, and anything else that doesn’t have demanding technical requirements.

These components can be absolutely crucial for a computer (especially the mouse and keyboard) but there isn’t a whole lot to say about them.

Peripheral Component Interconnect

While USB is the standard for connecting external components to your computer, the peripheral component interconnect or “PCI” connection is the generic connector for additional internal components. So while the CPU, RAM, and hard drive all use specialized connectors, the GPU, sound card, NIC, and a variety of other computer components use PCI.

Technically speaking, PCI is the name for an older, now-obsolete connection. It’s replacement—peripheral component interconnect express or “PCIe”—is now ubiquitous, so we can still get away with calling it just PCI.

Even More Components

So far I’ve talked about the components of your computer that actually do the work and number-crunching. Those components are usually the most interesting ones and the ones that superusers primarily concern themselves with. However there are other components concerned more with the practical matters of computers.

The components of a computer all communicate with each other using electrical signals, so naturally there must be a power supply for these components. Usually the power supply directly supplies power to the hard drive, GPU, and motherboard, and the motherboard then parcels out power to all the other components connected to it.

Like all electrical devices, computer components generate heat as a byproduct of their operation. Particularly power-hungry components like the CPU and GPU require their own cooling devices in order to continue operating correctly and not damage themselves during operation. Computers also often come with several fans to keep cool air circulating among all of the components.

Computers also have a variety of cases to which the parts attach and are enclosed by. Because of the traditional monolith-like case designs, computer cases are often called “towers”.

Lastly, remember that computer components come in all shapes and sizes. Your desktop computer, laptop, phone, tablet, video game console, and music player may all look and behave very differently but they are all computers at heart.

Exercises

- newegg.com and

pcpartpicker.com are online shops

catering to those who assemble their own computers. Try to put together a

shopping list of components for building your own computer. Take care to

ensure that the components you select are compatible with each other! Here’s

a checklist of what you’ll need:

- Case

- Motherboard

- CPU

- CPU heat sink (often included with CPU)

- RAM

- HDD/SSD

- GPU

- Optical drive (CD/DVD/Blu-Ray)

- Power supply

- Case fans

- If you’ve finished the previous exercise, try it again but restricted to a budget of $1,000. This is a reasonable budget for a decently powerful computer. Try to come up with the most powerful components for that budget. What decisions do you get to make regarding the sort of computer you’re building?